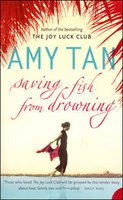

Amy Tan’s Saving Fish from Drowning is a masterpiece of irony – and yet another reminder that there is little as damaging to the world as American goodwill. If Edward Said’s Orientalism were ever transformed into a witty case study on the inability of East and West to understand each other, this might be it.

In Tan’s latest work we are invited to follow a party of twelve Americans off to the Orient on a “Following Buddha’s Footprints” itinerary which will take them to China and Burma. Only a few weeks before the scheduled departure, however, the group find themselves without their guide. Bibi Chen, a fifty something San Francisco socialite, whose philanthropy and love of the arts have turned her into a demi-celebrity in that arena, is found dead in her apartment. Escaped from China as a young girl just before the Revolution, she was the American’s gateway into understanding what they were about to see, their buffer against the inevitable faux-pas that follow over-confident tourists in exotic locations. But their loss is our gain. Instead of guiding her friends and acquaintances to the East, Bibi ends up guiding us, the readers, to the sometimes hilarious, sometimes-embarrassing behavior of westerners abroad. She is a wonderful tour leader and is further benefited by the incorporeal state she inhabits throughout the novel, which permits us to a look at rare locations inside the characters psyches. “It was not my fault” is the first sentence in the novel, one that instructs us to expect the worst from these people – and by the end no one can feel disappointed.

In casting her tour party, Tan reveals a deft hand in describing a certain type of American, in a way that is both instantly recognizable and most of the time, terribly funny. They are all well-off, some notoriously so, such as Harry, TV’s favorite dog trainer, his long time friend Moff, who has built a bamboo empire selling architectural plants to airports and luxury hotels, clients shared by Marlena who acquires art for the same locales. One, Wendy, is obscenely rich, an heiress who likes to rough it, and who agrees to the trip, encouraged by a former lover, who works for the NGO Free to Speak, and informs her on the practices of the brutal regime in Burma. Wyatt is her escort, and as his name suggests he’s a true blue Midwesterner, whose only concern is how to finance his (mostly) ecotourism. Dwight and Roxanne are a couple, both research investigators, and the difference in their academic careers is starting to strain their relationship (Roxanne is older, and more well-known and respected), although it doesn’t help that Dwight is exquisitely obnoxious. Vera is the venerable “elder” of the twelve, a fifty something African American intellectual, a soothing influence on the more histrionic characters. And Benny, who we might assume drew a cosmic short straw when he was invited to fill Bibi Chen’s walking shoes- the over sensitive gay, strives to please everyone and finds himself, of course, despised by most.

I left Heidi, Roxanne’s younger sister to the end, because I feel she is Tan’s most accomplished creation. In big breasted Heidi, the author gives us a taste of our own medicine, for she starts out as seemingly the silliest of the Americans, a hypochondriac, who read up on every possible health hazard, and never goes out without antibiotics, syringes, a space blanket, a head-lamp (and extra batteries), among other accoutrements. And she turns out to be the only one suitably prepared for the trip, the only one who believes her personality has room for improvement, and a calm presence during crisis.

They all have some things in common: mostly they prefer tracks and hikes to museums, or other cultural activities and all place importance on getting to know “real people” (as if there was such a thing as “false” people), and share the belief that “natives” are authentic, genuine, and therefore good and honest. Yes, there are also characters that show a superior openness of heart, honesty (even if it means being rude to the “natives”), and even a philosophical stance on the group’s difficulties. They are the children of the party, both on the verge of full blown adolescence and yet still displaying the more commendable side of humanity, Esmè, Marlena’s daughter and Rupert, Moff’s son.

To add to the irony, Tan soon shows us that not only do the Americans act based upon stereotypes of eastern culture, so do the Chinese and Burmese they encounter labor under similar misconceptions. In this passage Chen gives us a piece of Miss Rong’s, the Chinese guide’s mind:

She had heard that many Americans, especially those who travel to China, love Buddhism. She did not realize that the "Buddhism the Americans before her loved was Zen-like, a form of not thinking, not moving, and not-eating anything living, like buffaloes. This blank-minded Buddhism was practiced by well-to-do people in San Francisco and Marin County, who bought organic-buckwheat pillows for sitting on the floor, who paid experts to teach them to empty their minds of the noise of life".

Even an interest in the same forms of spirituality ends up losing East and West in the translation.

The main challenge with so many characters is to give them all equal time and opportunity to reveal themselves. Even though the book is 474 pages long I felt that Vera for one, and also Wyatt should have had more time on the narrative. Some reviewers seemed to think the disappearance takes place too late in the book (two thirds in to it), but I believe the book is to be read more for the character’s sake than the plot, and anyway a lot happens until you get there. If anything, the moment the Americans vanish, made by attention wander. I left the book aside for a couple of weeks, even though I had been devouring it until then.

Pascal Khoo Thwe called the oriental characters “wooden and stilted”, in his review for The Guardian, and initially I agreed. But having now finished the book I have a different opinion – Blackspot, Grease, Salt, Fishbones, Loot and Bootie- the Burmese we encounter don’t even have first names, but somehow it just doesn’t seem possible than Tan lost her abilities midway through the book. It is rather like she was trying to call attention to the interchangeability of these characters. They will change our main characters lives forever, their stories of persecution and torture are moving and yet, they will remain blurry and in some levels incomprehensible, until the end – kind of like the East to the West, and vice-versa.

The book poses a lot of questions such as the morality of tourism in countries with oppressive regimes, the lack of understanding between cultures, the role of the media in the construction of our world. But Tan she never provides any answers, probably because there aren’t any easy ones. As the narrator, Bibi, confesses:

"But when I was alive, I was not looking for tragedy. I was looking for bargains, the best places to eat, for pagodas that were not overrun with tourists, for the loveliest scenes to photograph".

For the time being, even if we don’t yet understand the language, maybe we should start by looking each other in the eyes.

No comments:

Post a Comment